Resource Hub

The GasFields Commission provides communities and landholders with the information and support they need to make informed decisions and achieve balanced outcomes. This Resource Hub houses all of the Commission’s publications, reports, fact sheets, useful links etc.

If you cannot find the resources you are looking for, or want more information please contact us via email.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQs)

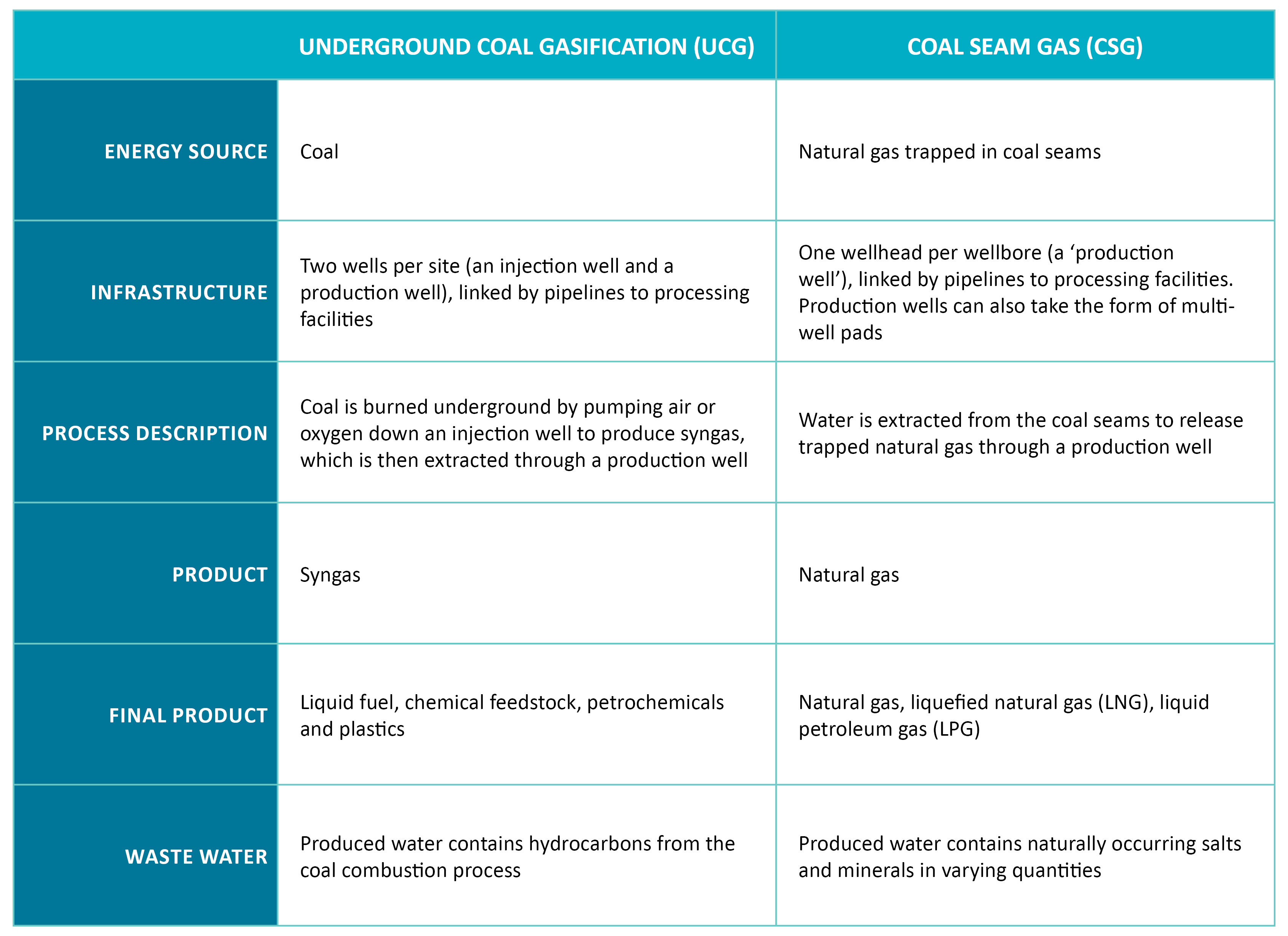

UCG and CSG production are two vastly different processes. While UCG and CSG both produce gas from coal deposits, the product gases they create are very different and applied to different end uses.

The Queensland Government has placed a moratorium on all future UCG exploration and development activities because of the unfavourable outcomes from the UCG trial projects undertaken in Queensland to date.

UCG is a process by which coal is burned in situ underground via a controlled combustion process to produce syngas—a mixture of various hydrocarbon gases, hydrogen and carbon monoxide. The exact composition of syngas depends on the coal type, operating pressure, combustion temperature, water concentration, and the oxidant used (air vs pure oxygen). Syngas is used as a chemical feedstock to produce various petrochemicals and plastics as well as a fuel for power generation.

The extraction of syngas is considered a mining activity and is governed under the Mineral Resources Act 1989. UCG is an unconventional coal mining activity, providing a way to extract energy from coal deposits that are uneconomical to mine using conventional methods.

In comparison, the extraction of CSG is a petroleum and gas extraction activity governed under the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004. CSG has been commercially produced safely in Queensland for more than 15 years and currently accounts for more than 70% of the state’s natural gas consumption. Table 1 (below) illustrates the difference between UCG and CSG.

![]() For more information download: Code of Practice – For the construction and abandonment of petroleum wells and associated bores in Queensland (Petroleum and Gas Inspectorate)

For more information download: Code of Practice – For the construction and abandonment of petroleum wells and associated bores in Queensland (Petroleum and Gas Inspectorate)

![]() Click for a range of relevant current CSG information available to landholders and regional communities via the Department of Environment and Science’s (DES) ‘Coal Seam Gas Information for Community and Landholders’ webpage.

Click for a range of relevant current CSG information available to landholders and regional communities via the Department of Environment and Science’s (DES) ‘Coal Seam Gas Information for Community and Landholders’ webpage.

![]() Click for more information on how DES helps manage and regulate various resource activities including petroleum (including oil and gas), greenhouse gas storage, coal seam gas water, fraccing and noise, light and odour issues.

Click for more information on how DES helps manage and regulate various resource activities including petroleum (including oil and gas), greenhouse gas storage, coal seam gas water, fraccing and noise, light and odour issues.

Conventional and unconventional petroleum resources

Petroleum resources are typically distinguished as ‘conventional’ or ‘unconventional’ based on the differences in the methods of extraction.

Conventional petroleum resources are oil and gas found in sandstone that can be extracted using traditional methods, and with few wells for each basin. The oil and gas resources are usually from another formation but move into the sandstone and are trapped by an impermeable ‘cap’ rock.

Conventional petroleum resources are extracted using traditional methods of drilling down through the ‘cap’ rock and allowing petroleum to flow up the well.

The resources that can be extracted from conventional petroleum reserves include crude oil, condensate and natural gas. The products that can be refined include liquefied petroleum gas, fuel oils, petrol, diesel, kerosene, asphalt base and others.

In Queensland, conventional petroleum reserves can be found in the Cooper and Eromanga Basins, Bowen and Surat Basins, and the Adavale Basin.

See below a short animation (prepared by GISERA) that explores what conventional gas is, how it is extracted and what are some of the challenges involved.

Unconventional petroleum resources are oil and gas found in a variety of rocks that need to be extracted using additional technology, energy or investment to release the resource from the source rock.

Unconventional resource development usually requires extensive well fields and more surface infrastructure using either multiple vertical wells and/or vertical wells in combination with horizontal or directional drilling. Examples of unconventional resources include coal seam gas (CSG), tight gas, shale gas and shale oil.

Shale gas is found in shale deposits and tight gas is found in relatively impermeable geological formations. Shale gas and tight gas refer to natural gas that has been trapped in low-fracture, low permeability formations that generally do not have a natural flow. These formations are located below 2,000 metres, much deeper than CSG resources.

Specialised technologies are needed to produce gas from these kinds of reservoirs such as directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing. The use of horizontal drilling technology also allows for multiple wells to be drilled from one well pad which can reduce the surface footprint.

The development of shale and tight gas resources is in its infancy in Australia. Whilst Queensland has these resources, activities are generally at the exploration stage

![]() NOTE: Hydraulic fracturing (‘fraccing’/‘fracking’) is a well stimulation technique used to increase the volumes of gas extracted from both conventional and unconventional wells, although it is most frequently used when drilling unconventional wells.

NOTE: Hydraulic fracturing (‘fraccing’/‘fracking’) is a well stimulation technique used to increase the volumes of gas extracted from both conventional and unconventional wells, although it is most frequently used when drilling unconventional wells.

![]() For more information see FAQ: ‘What is hydraulic fracturing (‘fraccing’/‘fracking’), what chemicals are used and how are they regulated?’

For more information see FAQ: ‘What is hydraulic fracturing (‘fraccing’/‘fracking’), what chemicals are used and how are they regulated?’

Types of unconventional gas

Australia has vast resources of unconventional gas including CSG, shale gas, and tight gas. Currently, only CSG is being developed in Queensland.

CSG production in Queensland

Queensland has two basins currently producing CSG, the Bowen and Surat basins. A number of other basins have potential and are currently being explored.

For further information about CSG production in Queensland, refer to the Queensland Government website Petroleum and coal seam gas.

In Queensland, a petroleum resource authority is required under the Petroleum and Gas (Production & Safety) Act 2004 to explore for and produce gas.

Emissions of methane from physical infrastructure (e.g. well heads, processing equipment and pipelines) and from operational losses are known as ‘fugitive’ emissions. Fugitive emissions by their very nature are often difficult to measure directly. An initial CSIRO study titled Fugitive Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Coal Seam Gas Production in Australia (‘Emissions from CSG Production’), estimated fugitive emissions at between 1.3 to 4.4% of gas production. Research is continuing to develop better methodologies in estimating these fugitive emissions and their contribution to greenhouse gas emissions.

The ‘Emissions from CSG Production’ research investigated fugitive emissions from 43 CSG production wells across Queensland and New South Wales. The CSIRO found that the average fugitive emission rate from all sources on the well pads was about 0.02% of total gas production.

A key focus of industry and regulation is gas well integrity to ensure the design, construction, operation and maintenance of gas wells will maximise gas production and minimise the level of fugitive emissions.

The industry must abide by the Code of Practice for the construction and abandonment of petroleum wells and associated bores in Queensland and the Code of Practice for Upstream PE Gathering Lines in the CSG Industry.

Historical evidence from coal rich areas in Queensland, such as the Surat and Bowen basins, shows that natural gas seepages from the landscape are a naturally occurring phenomenon that predate the development of the Coal Seam Gas (CSG) industry.

The Gas Industry Social and Environmental Research Alliance (GISERA) has conducted a ‘Whole of life cycle greenhouse gas assessment’ research project to detect and measure methane seeps in the Surat Basin to provide a baseline of methane emissions on a regional scale. This data set has been used as a benchmark when comparing changes in methane concentrations over time as CSG production increases throughout the Surat Basin.

Types of impacts

The construction and installation of onshore gas industry infrastructure may cause localised environmental disturbance, including soil degradation, contamination and the introduction of invasive species due to the project area footprint and the heavy machinery involved. Impacts can materialise in various forms, including but not limited to:

- Ground disturbances – may include the location of gas wells, well pads, pipelines, access roads and laydown yards (see Gas Guide – Chapter 7)

- Business impacts – e.g. changes in yield resulting from construction, operation, decommissioning and rehabilitation of gas activities (see Gas Guide – Chapter 5)

- Groundwater impacts – the removal of groundwater during the gas extraction process may lead to water bores, located in the same aquifer, being impacted (see Gas Guide – Chapter 6)

- Noise, light, dust and odour impacts – these may arise during construction and operation of gas infrastructure and are managed via the resource companies Environmental Authority (EA), issued by the Department of Environment and Science (DES) (see Gas Guide – Chapter 7).

The GasFields Commission’s Gas Guide and Roadmap have been specifically collated to deliver landholders a clear and easy to understand guide of what to expect during each stage of engagement with petroleum and gas developments, on private land, in Queensland – including detailed information around the management of possible impacts.

![]() Download the Gas Guide and Roadmap for more information.

Download the Gas Guide and Roadmap for more information.

Minimising the impacts of a resource company’s activities on your property is a realistic but challenging goal. Queensland’s Land Access Code, made under the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004, provides advice on best practice communication, consultation and negotiation.

Protection of agricultural land

In Queensland, agricultural land is protected by environmental and regional planning legislation. These protections do not aim to prevent resource development. They do however seek to manage the impact of resource activities and other regulated activities on areas of regional interest; and support coexistence of resource activities with other activities, including highly productive agricultural activities.

The purpose of the Regional Planning Interests Act 2014 (RPI Act) is to identify areas of Queensland that are of regional interest because they contribute, or are likely to contribute, to Queensland’s economic, social and environmental prosperity. The RPI Act also manages the impacts of resources activities in areas of regional interest to maximise the opportunity for coexistence.

To achieve its purposes, the RPI Act provides for a transparent and accountable process for the impact of proposed resource activities and regulated activities on areas of regional interest to be assessed and managed.

The RPI Act manages impacts of resource activities in the following areas:

- Priority agricultural areas (PAAs)

- Priority living areas (PLAs)

- Strategic cropping areas (SCAs)

- Strategic environmental areas (SEAs).

The purpose of identifying PAAs, PLAs and SCAs is to ensure that resource activities in these areas do not hinder agricultural operations. They must not result in a material impact on a priority agricultural land use. The assessment criteria in the Regional Planning Interests Regulation 2014 provide prescribed solutions for managing impact.

If a resource company wishes to operate in areas defined under the RPI Act, it must factor in the priority land use interests when negotiating a Conduct and Compensation Agreement (CCA) with a landholder. Any new resource development seeking to operate in a PAA will need to meet assessment criteria ensuring no material loss of land, no threat to continued agricultural use and no material impact on declared regionally significant irrigation aquifers or overland flow.

Several guidelines have been developed to provide more information about the RPI Act. You can access these guidelines and associated maps by visiting the Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning website: www.statedevelopment.qld.gov.au.

![]() GasFields Commission Queensland have delivered seven recommendations to the State Government as part of its “Review of the Regional Planning Interests Act 2014 Assessment Process Report”.

GasFields Commission Queensland have delivered seven recommendations to the State Government as part of its “Review of the Regional Planning Interests Act 2014 Assessment Process Report”.

Environmental Authority

In Queensland, resource companies need to apply for an EA before undertaking an environmentally relevant activity (ERA). ERAs are industrial, resource or intensive agricultural activities with the potential to release contaminants into the environment. They include a wide range of activities such as aquaculture, sewage treatment, cattle feedlotting, mining and resource activities such as petroleum (which includes coal seam gas), geothermal and greenhouse gas storage activities.

The purpose of an EA is to protect sensitive receptors such as houses, ecosystems and areas of environmental value from resource activity. The EA is issued by DES and provides conditions to minimise the effects environmental nuisance and establishes limits on activities that could cause environmental harm.

Where a resource activity will result in significantly disturbed land, DES may require an EA holder to pay financial assurance (FA). FA is a type of financial security provided to the Queensland Government to cover any costs or expenses incurred in taking action to prevent or minimise environmental harm or rehabilitate or restore the environment, should the EA holder fail to meet their environmental obligations.

Subject to successful rehabilitation and the EA holder meeting their closure conditions, FA is returned at the end of the project. For further information on FA, including when FA may be required and how it is calculated, refer to the Business Queensland website: www.business.qld.gov.au.

Soil impacts

The footprint of Coal Seam Gas (CSG) development on agricultural lands and the environment is acknowledged as much greater than the proportionally small area devoted to the well head infrastructure, or even surrounding lease areas during development. The extent and nature of damage to the soil resource caused by the various elements involved in the development of the CSG industry is not currently well documented.

Numerous academic studies have been undertaken on the impact to agricultural soil as a result of the development and operation of the CSG industry. To date the studies have centred around assessing the extent of damage to agricultural soil caused by the various elements of CSG development.

One such study undertaken in 2014 – ‘Quantifying the impacts of coal seam gas (CSG) activities on the soil resource of agricultural lands in Queensland, Australia‘ – focused on the impacts on soil in the Surat and Bowen basins. The paper examined the importance of quantifying the different impacts that CSG activities have on soils in order to better inform the development of gas industry guidelines to minimise impacts to the soil resource on joint CSG–agricultural lands.

Another study, undertaken by the Gas Industry Social and Environmental Research Alliance (GISERA) – ‘The effects of coal seam gas infrastructure development on arable land. Project 5: Without a trace (Final report)‘ – undertook a study of farms in the Surat Basin. This research drew from an evidence-based understanding of regional processes and issues relating to five key topics:

- Surface and groundwater;

- Biodiversity;

- Agricultural land management;

- Marine environment; and

- Socio-economic impacts.

The work reported in GISERA’s study was conducted under the agricultural land management theme to extend the knowledge-base of environmental impacts and management associated with development of CSG infrastructure, and to assist the industry meeting the expectations of stakeholders and the wider farming community.

This study also works to inform land managers and the CSG industry on ways to improve current operations and protect the soil resource. Therefore, the objectives of this research were to:

- Assess the damage to agricultural soils associated with development of CSG infrastructure

- Model the likely impact of soil compaction on crop productivity

- Acquire a background dataset, which may be used to advise policy makers and the CSG industry on measures relating to improved soil management practices within highly-productive arable land in Queensland.

Weed management

All Queenslanders have a ‘general biosecurity obligation’ under the Biosecurity Act 2014. Regardless of resource activity in your local area, landholders should have a biosecurity management plan, which would include an on-farm biosecurity plan to protect their day-to-day business operations from threats posed by invasive weeds – this should be in addition to the tenure holder’s biosecurity plan.

![]() Download the GFCQ Biosecurity Checklist: A guideline for landholders and resource companies.

Download the GFCQ Biosecurity Checklist: A guideline for landholders and resource companies.

The Biosecurity Act 2014 ensures a consistent, modern, risk-based and less prescriptive approach to biosecurity in Queensland. The Act provides comprehensive biosecurity measures to safeguard our economy, agricultural and tourism industries, environment and way of life, from:

- pests (e.g. wild dogs and weeds)

- diseases (e.g. foot-and-mouth disease)

- contaminants (e.g. lead on grazing land).

The Act replaced the many separate pieces of legislation that were previously used to manage biosecurity. Decisions made under the Act will depend on the likelihood and consequences of the risk. This means risks can be managed more appropriately. Under the Act, the Biosecurity Regulation 2016 sets out how the Act is implemented and applied.

Landholders can help prevent weed spread by regularly cleaning vehicles and equipment, ensuring weed hygiene declarations accompany seed stock and fodder, adopting quarantine procedures before introducing new livestock and maintaining pastures in good conditions. They can benchmark their weed status and establish risk management practices, ideally prior to any significant gas activity on their property.

A good reference for landholders wanting more information on managing weed spread is a white paper presented at the Nineteenth Australasian Weeds Conference, titled ‘Agriculture, big business and the gas fields: practical tools for weed hygiene at the mega-scale‘. This white paper discusses weed prevention measures/strategies developed by the onshore gas industry as part of standard operating procedures.

The measures include landholders’ practices; legislation; and weed hygiene procedures adopted by the onshore gas industry. The strategies help to find collaborative weed management solutions with other industry partners and to guide biosecurity management planning, hygiene management planning and practices and land access agreement negotiations.

The Land Access Code, made under the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004, imposes mandatory conditions concerning the conduct of authorised activities, including petroleum authorities, on private land. One of the mandatory conditions (section 15 of the Code) is to prevent the spread of a declared pest while carrying out authorized activities. A declared pest is defined under the Biosecurity Act 2014 and can also be an animal or plant declared under a local law to be a pest.

Visit the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries’ Farm Biosecurity Program website (www.farmbiosecurity.com.au) for detailed information on how to identify and understand biosecurity risks, minimise the spread of pests, weeds and diseases and what landholders can do to assist meeting their ‘general biosecurity obligation’.

Part of the Farm Biosecurity Program’s suite of tools for landholders to control biosecurity risks is the Farm Check-In app – a tool used for visitors to help identify potential biosecurity risks and minimise the spread of pests and diseases when entering an agricultural property.

![]() To investigate current gas development activities, visit the GFCQ Interactive Gas Map which gives you access to view and download geospatial data/information relating to Queensland’s onshore gas industry activities in your local area.

To investigate current gas development activities, visit the GFCQ Interactive Gas Map which gives you access to view and download geospatial data/information relating to Queensland’s onshore gas industry activities in your local area.

Various dispute resolution options are available if negotiations with resource companies become challenging or stall completely. The GasFields Commission’s recommendation, which is supported by experts in negotiation and issue resolution, is to keep the lines of communication open.

If the parties are unable to reach an agreement on their own, the resource company can issue a notice of intent to negotiate (NIN) which allows them to proceed through the statutory negotiation processes available.

Slight differences, such as time frames and requirements, exist between the process for negotiating Conduct and Compensation Agreements (CCAs) compared to Make Good Agreements (MGAs).

However the general resolution options available for the two types of agreements are similar as outlined in the diagrams below.

Either party can seek to enter into a dispute resolution process by providing written notice to the other. Some of the dispute resolution options available in Queensland include:

- Conference – An authorised officer from the Department of Resources (Resources) facilitates discussions between the parties with the aim of reaching agreement usually within 20 business days for CCAs or 30 business days for MGAs. This is a low-cost, nonbinding option.

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)

- Facilitative Mediation – an independent person facilitates a discussion between the parties. The mediator is impartial and does not advise or make any decisions.

- Evaluative Mediation – a process which may include an assessment by the mediator of the strengths and weaknesses of the parties’ cases and a prediction of the likely outcome of the case.

- Conciliation – an independent person who is an expert on the subject provides advice on the strengths and weaknesses of each side of the dispute. While the conciliator provides advice, they do not make any decisions.

- Case Appraisal – an independent person who is an expert receives evidence from each party. The case appraiser assesses the merits of each case and makes a non-binding decision in writing.

- Arbitration – involves an independent and suitably qualified third party acting as a judge. Both parties must agree to the choice of the arbitrator.

- Land Court of Queensland hearing – These are public hearings and the decision of the Land Court is binding. An application can also be made to the Land Court to decide a dispute in relation to a MGA if a conference or an ADR was held and either not concluded or failed to reach agreement.

The information shared during any of these ADR processes is maintained as confidential. ADRs are initiated by completing a form known as an Election Notice – click to download a copy of the ADR Election Notice.

![]() For dispute resolution regarding potential breaches after “agreements are in place”, either party can contact the Land Access Ombudsman.

For dispute resolution regarding potential breaches after “agreements are in place”, either party can contact the Land Access Ombudsman.

![]() Landholders wishing to lodge complaints about pollution or noise, light and odour issues should contact the Department of Environment and Science.

Landholders wishing to lodge complaints about pollution or noise, light and odour issues should contact the Department of Environment and Science.

![]() It is important to note the GasFields Commission does not ENGAGE in individual negotiations between landholders and resource companies, nor does it INVESTIGATE complaints made against individual resource companies.

It is important to note the GasFields Commission does not ENGAGE in individual negotiations between landholders and resource companies, nor does it INVESTIGATE complaints made against individual resource companies.

Landholders wishing to lodge complaints about resource exploration or development activities should contact the Department of Resources’ Resource Community Infoline:

- Phone: 13 71 07

- Email: resources.info@resources.qld.gov.au

- Web (to lodge a complaint): https://www.resources.qld.gov.au/business/mining/resources-complaints-form.

The GasFields Commission’s Gas Guide and Roadmap have been specifically collated to deliver landholders a clear and easy to understand guide of what to expect during each stage of engagement with petroleum and gas developments, on private land, in Queensland – including detailed information around what dispute resolution options are available if negotiations with resource companies become challenging or stall completely (see Chapter 10 – Dispute Resolution). Download the Gas Guide and Roadmap for more information.

What is CSG produced water?

The groundwater that is removed from coal seams in order to produce CSG is known by several different names, including CSG produced water, co-produced water, associated water and CSG water (for consistency the Commission will be using the term ‘CSG produced water’ throughout this site). This water can be treated and used beneficially for a range of purposes.

The Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 defines ‘produced water’ as “CSG water; or associated water for a petroleum tenure. In the act, reference to produced water includes – treated and untreated CSG water, and concentrated saline water produced during the treatment of CSG water”.

CSG produced water contains natural salts and other minerals in varying quantities. Some of the groundwater extracted to produce CSG in Queensland is treated to ensure that it meets the quality standards and environmental guidelines for its intended reuse purpose.

In Queensland, CSG produced water is used for crop irrigation, livestock watering, industrial manufacturing, dust suppression and for the construction of onsite gas field infrastructure. CSG produced water is also reinjected into groundwater aquifers for future use. The treatment and reuse of CSG produced water is strictly regulated.

In Queensland, resource companies have the right to take ‘associated water’ (CSG produced water) under Part 4 of the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 and Part 6D, Division 5, Subdivision 2 of the Petroleum Act 1923 – as water is a by-product in the process of extracting gas.

In addition, resource companies have an obligation to comply with the underground water management framework under Chapter 3 of the Water Act 2000.

![]() For more information on the types, uses and regulation of CSG produced water in Queensland, visit the Department of Environment and Science website: www.environment.des.qld.gov.au.

For more information on the types, uses and regulation of CSG produced water in Queensland, visit the Department of Environment and Science website: www.environment.des.qld.gov.au.

Regulation

- The Waste Reduction Recycling Act 2011 recognises that CSG produced water, which is a ‘waste’ under the Environmental Protection Act 1994, may have beneficial uses. This Act prescribes the process whereby CSG produced water can be reclassified as a resource and used for a beneficial purpose.

- The Environmental Protection Act 1994 imposes requirements on the management of CSG produced water, including its use, treatment, storage and disposal.

- The Coal Seam Gas Water Management Policy 2012 encourages resource companies to manage CSG produced water in a way that benefits regional communities and reduces impacts on the environment.

Until recently, the beneficial use of CSG produced water needed to be approved by the Queensland Government under a ‘Beneficial Use Approval’. While some of these approvals are still in effect until they expire, recent legislative changes have introduced ‘End of Waste’ approvals and codes that allow for CSG produced water to be used for beneficial purposes.

The main drive for this change was to reduce the regulatory burden on a by-product (e.g. CSG produced water) that fits the criteria to be deemed a ‘resource’ instead of a ‘waste’. For CSG produced water to be deemed a resource, trials must be conducted to demonstrate it meets a set of requirements. If the CSG produced water meets these requirements and is deemed a resource, further regulatory approvals for its use would not be required.

![]() For more information on the End of waste (EOW) framework, visit the Department of Environment and Science website: www.environment.des.qld.gov.au.

For more information on the End of waste (EOW) framework, visit the Department of Environment and Science website: www.environment.des.qld.gov.au.

Case Study

The Chinchilla Beneficial Use Scheme is an example of CSG water being put to a beneficial use. It is a contractual arrangement between Queensland Gas Company (QGC) and SunWater, a bulk water infrastructure developer and manager.

QGC treats CSG produced water from its gas fields in the Surat Basin at its Kenya Water Treatment Plant south west of Chinchilla. The Kenya WTP treats and recovers approximately 90% of the raw CSG produced water and transports it by pipeline directly to landholders and to the Chinchilla Weir on the Condamine River, where it is mixed with river water and supplements water reserves available for agricultural use and public consumption.

Source: GasFields Commission Queensland (QGC Kenya Water Treatment Plant [2021])

Salt and brine

The treatment of CSG produced water using desalination technologies results in brine and, ultimately, salt residues that must be appropriately managed. The concentration and composition of salts depends on the characteristics of the CSG produced water and the treatment process.

The salinity of CSG produced water is typically measured as the concentration of total dissolved solids (TDS) with values ranging from 200 to more than 10,000 milligrams per litre.

By comparison, good quality drinking water has TDS value of less than 500 milligrams per litre. The TDS of sea water is between 36,000 and 38,000 milligrams per litre. Brine is defined as saline water with a total dissolved solid concentration greater than 40,000 milligrams per litre.

The Coal Seam Gas Water Management Policy 2012—ESR/2016/2381 (formerly EM738) requires that saline waste is managed in accordance with the following two priorities:

- Priority 1 — Brine or salt residues are treated to create useable products wherever feasible.

- Priority 2 — After assessing the feasibility of treating the brine or solid salt residues to create useable and saleable products, disposing of the brine and salt residues in accordance with strict standards that protect the environment.

![]() For more information on the long-term management strategy for brine and salt, visit the Department of Environment and Science website: www.environment.des.qld.gov.au.

For more information on the long-term management strategy for brine and salt, visit the Department of Environment and Science website: www.environment.des.qld.gov.au.

What is hydraulic fracturing (‘fraccing’/‘fracking’)?

Hydraulic fracturing, also commonly referred to as ‘fraccing’ or ‘fracking’, is a method used to stimulate gas production from geological formations with a low permeability. Typically only a small fraction of wells drilled in Queensland are hydraulically fractured, as this process adds considerable expense to the cost of gas production. It is only undertaken when absolutely necessary based on challenging geological conditions.

Hydraulic fracturing involves injecting fluid made up of water, sand and chemical additives into a target gas formation to fracture the rock to release the oil and gas. Hydraulic fracturing is primarily used in the production of shale gas and tight gas. However, it is also used in the production of CSG from deeper, lower permeability coal seams.

How are hydraulic fracturing activities regulated?

The Department of Environment and Science (DES) has established model conditions for an Environment Authority that specify the management requirements for hydraulic fracturing activities in coal seam gas wells – the Streamlined model conditions for petroleum activities—ESR/2016/1989 (streamlined conditions).

Assisting DES in improving decision making time frames, the streamlined conditions are outcomes-focused and provide for transparency and consistency across the petroleum and gas industry.

What chemicals are used in hydraulic fracturing?

Water (84 – 96%) proppant (3 – 15%), such as sand, make up around 99% of the hydraulic fracturing fluid. Added chemicals make up about 1% of the hydraulic fracturing fluid – these chemical additives are used to reduce friction, inhibit bacteria growth, dissolve minerals and enhance the hydraulic fracturing fluid’s ability to transport sand into fractures.

Some commonly used chemical additives, and their uses in hydraulic fracturing fluids, include:

- guar gum (a food thickening agent) is used to create a gel that transports sand through the fracture;

- bactericides, such as sodium hypochlorite (pool chlorine) and sodium hydroxide (used to make soap), are used to prevent bacterial growth that contaminates gas and restricts gas flow;

- ‘breakers’, such as ammonium persulfate (used in hair bleach), that dissolve hydraulic fracturing gels so that they can transmit water and gas;

- surfactants, such as ethanol and the cleaning product orange oil, are used to increase fluid recovery from the fracture; and

- acids and alkalis, such as acetic acid (vinegar) and sodium carbonate (washing soda) to control the acid balance of the hydraulic fracturing fluid.

![]() A comprehensive list of the most commonly used additives in hydraulic fracturing fluid can be found in Appendix A of the GasFields Commission’s ‘Shared Landscapes – Industry Trends’ Report.

A comprehensive list of the most commonly used additives in hydraulic fracturing fluid can be found in Appendix A of the GasFields Commission’s ‘Shared Landscapes – Industry Trends’ Report.

NOTE: In Australia, it is mandatory for resource companies to release a full list of the chemical compounds used during drilling and hydraulic fracturing operations. Resource companies in Queensland are, under the State’s existing regulatory frameworks, required to disclose a full list of additives prior to any hydraulic fracturing activities commencing.

How are hydraulic fracturing chemicals regulated?

- The Environmental Protection Act 1994 was amended in October 2010 to regulate the use of benzene, toluene, ethyl-benzene and xylenes (BTEX) chemicals in hydraulic fracturing processes. As BTEX chemicals occur naturally in underground water sources, the government has restricted the use of BTEX in hydraulic fracturing processes to maintain nationally set environmental and human health standards.The amendments to the Act also improved notice requirements of incidents that may cause serious or material environmental harm to affected landholders. Affected landholders must also be notified of incidents that may cause serious or material environmental harm.The use of BTEX chemicals in hydraulic fracturing fluids in Queensland is strictly prohibited under section 206 of the Environmental Protection Act 1994.

- The Petroleum and Gas (Safety) Regulation 2018 and Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 stipulate a resource companies are required to notify the government and landholders when carrying out hydraulic fracturing activities at least 10 business days before commencement, and when completing hydraulic fracturing by submitting a notice of completion within 10 days of completion.Companies must lodge a report with the Queensland Government, within two months of any hydraulic fracturing activity, detailing the composition of the fracturing fluid used at each well and its potential impact. These detailed completion reports are made available to the public after five years.

![]() For more information on BTEX chemicals and disposal of fraccing fluids visit the Department of Environment and Science website: www.environment.des.qld.gov.au.

For more information on BTEX chemicals and disposal of fraccing fluids visit the Department of Environment and Science website: www.environment.des.qld.gov.au.

![]() For more information on hydraulic fracturing techniques, including reporting requirements and governance arrangements, visit the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment website: www.awe.gov.au.

For more information on hydraulic fracturing techniques, including reporting requirements and governance arrangements, visit the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment website: www.awe.gov.au.

![]() For more general information on hydraulic fracturing, visit CSIRO’s Gas Industry Social and Environmental Research Alliance (GISERA) website: https://gisera.csiro.au.

For more general information on hydraulic fracturing, visit CSIRO’s Gas Industry Social and Environmental Research Alliance (GISERA) website: https://gisera.csiro.au.

During the process of producing coal seam gas (CSG), groundwater is extracted in order to reduce water pressure in the coal seams to allow methane gas to be released from the coal. When water is extracted from a CSG well, groundwater pressure may fall in the area surrounding the well.

Holders of a petroleum tenure (resource companies) are required to manage these impacts on groundwater availability. In areas of concentrated gas development where there are multiple petroleum tenures, and more than one tenure holder working adjacent to each other, the chief executive responsible for administering Chapter 3 of the Water Act 2000 may declare a cumulative management area (CMA).

The Office of Groundwater Impact Assessment (OGIA) is an independent entity responsible for assessing and managing the impacts of groundwater extraction from resource operations (petroleum and gas, and mining) in cumulative management areas (CMAs). CMAs are declared where impacts from resource development may overlap.

There is one CMA in Queensland—the Surat CMA, which provides for ongoing assessment and management of cumulative impacts from petroleum and gas development. The Surat CMA (view map) was established in 2011, primarily in response to coal seam gas development.

The video above provides an introductory overview of the Surat CMA.

(download video transcript)

Video above explains how groundwater impacts may occur in aquifers surrounding CSG formations in the Surat Basin.

(download the video transcript)

OGIA are also responsible for preparing a cumulative assessment of impacts of CSG water extraction, and developing integrated regional management arrangements. These assessments and management arrangements are set out in OGIA’s underground water impact report (UWIR).

The UWIR for the Surat CMA is a statutory report to provide:

- an assessment of cumulative impacts from existing and proposed groundwater extraction by resource tenure holders;

- proactive strategies for managing those impacts (e.g. make good of water supply bores, monitoring strategy, impact mitigation strategies for affected springs); and

- assignment of responsibilities to individual tenure holders to implement strategies and ongoing reporting.

The resource activities that are called in the Surat CMA are coal seam gas, conventional oil and gas, and coal mining. The assessment is completed every 3 years in order to keep up to date with changes to industry development plans and new information about the groundwater flow system

What is Aquifer connectivity?

Aquifer connectivity refers to the ease with which groundwater can flow within and between geological formations. Research shows there is low aquifer connectivity (low vertical permeabilities) between the Surat, Bowen and Galilee Basins, and that water flow between the formations in these basins is extremely slow.

Water flows from areas of higher water pressure to areas of lower water pressure. When this hydrological system is disturbed by activities such as groundwater extraction, the water pressures underground and the direction of water flow may alter, which in turn may result in a change to aquifer water levels.

![]() For more details on water impacts relating to CSG activities, visit the Department of Environment and Science website: www.environment.des.qld.gov.au.

For more details on water impacts relating to CSG activities, visit the Department of Environment and Science website: www.environment.des.qld.gov.au.

![]() For more details on the current research into aquifer connectivity, visit the University of Queensland’s Centre for Natural Gas website: https://natural-gas.centre.uq.edu.au.

For more details on the current research into aquifer connectivity, visit the University of Queensland’s Centre for Natural Gas website: https://natural-gas.centre.uq.edu.au.

Assessment of subsidence

Following legislative amendments, the Department of Environment and Science amended guidance material for the preparation of the Office of Groundwater Impact Assessment’s (OGIA) Underground Water Impact Reports (UWIRs) and included a requirement for risk-based assessment of impacts on environmental values (EVs), that may result from subsidence caused by associated water extraction.

The UWIR is required to assess subsidence impacts that may have already occurred and are likely to occur in the future. Potential impacts to EVs that could result from land subsidence include changes to surface water flows that support aquatic ecosystems, impairment of aquifer integrity, and changes to ground slopes which may impair cropping lands.

Since late 2020, matters relating to subsidence have gained significant attention from landholders of cropping lands on the western edge of the Condamine Alluvium. In particular, there are concerns about how baseline conditions can be established in cultivated areas, whether subsidence may have already occurred as a result of CSG development, and how subsidence can be remediated or managed, where there is material change.

In response to these emerging concerns, OGIA, in collaboration with the GasFields Commission Queensland, established an ongoing engagement process with landholders and commenced several research initiatives to improve assessment methods and the collective understanding of subsidence. The improvements specifically relate to addressing the difficulty of establishing a baseline in cropping lands, developing a monitoring strategy to identify CSG-induced subsidence, and improving the predictions of subsidence.

![]() OGIA’s modelling of subsidence predicts that most of the cropping area around the Condamine Alluvium is likely to experience <100 mm of subsidence, with a maximum change in slope for most areas of less than 0.001% (10 mm per km) and up to 0.004% (40 mm per km) for some areas.

OGIA’s modelling of subsidence predicts that most of the cropping area around the Condamine Alluvium is likely to experience <100 mm of subsidence, with a maximum change in slope for most areas of less than 0.001% (10 mm per km) and up to 0.004% (40 mm per km) for some areas.

![]() For further information on OGIA’s ‘Assessment of subsidence’ download the 2021 Underground Water Impact Report (see Chapter 7 – Assessment of subsidence).

For further information on OGIA’s ‘Assessment of subsidence’ download the 2021 Underground Water Impact Report (see Chapter 7 – Assessment of subsidence).

Preliminary Activities

Preliminary activities are defined on the basis that they have no impact or only a minor impact on the land use or business activities of a landholder. While classified as low impact, early discussion around these types of activities provide opportunities for building the relationship between a landholder and resource company through its field-based representatives. Preliminary activities are also sometimes referred to as ‘scouting’ or ‘surveying’ and are generally associated with exploration. These activities may include:

- Walking the area of the designated resource authority

- Driving along an existing road or track in the area

- Taking soil or water samples

- Geophysical surveying not involving site preparation

- Aerial, electrical or environmental surveying

- Survey pegging.

However, the above are not considered preliminary activities if they are carried out on:

- Land that is being used for intensive farming or broadacre agriculture that is less than 100ha in size

- Organic or bioorganic farms.

![]() For more information on the requirements that apply to resource companies when entering private land (within the area of their resource authority) to undertake preliminary activities, visit the Business Queensland website: www.business.qld.gov.au.

For more information on the requirements that apply to resource companies when entering private land (within the area of their resource authority) to undertake preliminary activities, visit the Business Queensland website: www.business.qld.gov.au.

Advanced Activities

Advanced activities by a resource company are assessed as having direct impacts on a landholder’s business and land use activities. This can occur during exploration, production, laying of pipeline or other gas related activity such as the drilling of water monitoring bores. Advanced activities that could be undertaken by a resource company include:

- Constructing drilling pads and digging sumps

- Drilling of petroleum and gas wells

- Removal of vegetation

- Construction of temporary camp for workers, concrete pad, sewage/water treatment facilities or a fuel dump

- Geophysical surveying with physical clearing

- Construction of water treatment facilities or gas compression facilities

- Construction of a track or access road

- Changing a fence line.

Resource companies must comply with the mandatory conditions of the Land Access Code when carrying out authorised activities on a landholder’s private land. These conditions cannot be altered or waived by agreement. All parties are encouraged to comply with the code’s ‘best practice recommendations‘.

![]() For more information on the requirements that apply to resource companies when entering private land (within the area of their resource authority) to undertake advanced activities, visit the Business Queensland website: www.business.qld.gov.au.

For more information on the requirements that apply to resource companies when entering private land (within the area of their resource authority) to undertake advanced activities, visit the Business Queensland website: www.business.qld.gov.au.

The Gas Guide

The GasFields Commission’s Gas Guide brings together all the information landholders need to know about gas development into one concise, easy to read document – detailing everything from the awarding of exploration permits, Land Access and Make Good Agreements, right through to gas field rehabilitation.

The Gas Guide and Roadmap have been specifically collated to deliver landholders a clear and easy to understand guide of what to expect during each stage of engagement with petroleum and gas developments, on private land, in Queensland – including detailed information on what landholders can expect from both preliminary and advanced activities (see Chapter 4 – Engagement Phase). Download the Gas Guide and Roadmap for more information.

![]() To investigate current gas development activities, visit the GFCQ Interactive Gas Map which gives you access to view and download geospatial data/information relating to Queensland’s onshore gas industry activities in your local area.

To investigate current gas development activities, visit the GFCQ Interactive Gas Map which gives you access to view and download geospatial data/information relating to Queensland’s onshore gas industry activities in your local area.

Mineral and energy resources found in Queensland are not owned by individuals or companies, regardless of who owns the land over which the resource lies. The Queensland Government owns and manages these resources for the benefit of all Queenslanders. Legislation provides for the payment of royalties to the Queensland State Government and provides for a process that must be followed in relation to land access, conduct and compensation to owners and occupiers of private land.

![]() Under Queensland law, landholders cannot say “no” to gas activity on their property, nor do they have the right to prevent a resource authority holder from accessing their property to undertake authorised activities.

Under Queensland law, landholders cannot say “no” to gas activity on their property, nor do they have the right to prevent a resource authority holder from accessing their property to undertake authorised activities.

However, Queensland land access laws establish the requirements for resource companies to access private land to undertaken their activities. The Land Access laws require the following:

- A company cannot enter restricted land with the written consent of the landholder;

- A company must give an entry notice before entry to undertaken ‘preliminary’ (minor impact) activities;

- A Conduct and Compensation Agreement, Deferral Agreement or Opt-Out Agreement must be negotiated before a company comes onto a landholder’s land to undertake ‘advanced activities’ i.e., those likely to have more than a minor impact;

- If an agreement cannot be reached, a process for dispute resolution including a requirement formal dispute resolution to take place, and matters to be referred to the Land Court; and

- Companies must comply with the Land Access Code.

The Land Access Code includes best practice guidelines for landholders and resource companies about how to establish good relations, and mandatory conditions relating to matters of biosecurity and general conduct that resource companies must comply with when undertaking authorised activities on private land.

![]() For more information download ‘A guide to land access in Queensland’

For more information download ‘A guide to land access in Queensland’

What are deviated wells?

Traditionally, coal seam gas (CSG) wells are drilled straight down. These are known as vertical wells. Where conditions allow, resource companies may use ‘deviated’ wells – these are wells that are drilled at angles away from vertical.

Deviated drilling often involves drilling multiple, deviated wells from one surface location resulting in a ‘multi-well pad’ instead. Deviated drilling allows resource companies to reach the same amount of gas underground from a much smaller area on the surface.

![]() Download Arrow Energy’s ‘Deviated Drilling’ fact sheet.

Download Arrow Energy’s ‘Deviated Drilling’ fact sheet.

What is directional drilling?

Directional drilling (sometimes referred to as deviated drilling [see above]) involves drilling wells at non-vertical and non-horizontal angles. Directional drilling allows a resource company to intersect target formations where vertical wells are not possible or practical. Directional wells are also used where multiple wells are drilled from the same well pad location, referred to as a ‘multi-well pad’.

CSG wells are directionally drilled for several purposes, including:

- Drilling into a reservoir where vertical access is difficult or not possible – e.g. where a gas reserve is located under a town, under a lake, or underneath a difficult-to-drill geographic formation;

- Increasing the exposed section length through the reservoir by drilling through the reservoir at an angle; and

- Allowing more wells to be grouped together on one surface location can allow fewer rig moves, less surface area disturbance, and make it easier and cheaper to complete and produce the wells (see above ‘multi-well pad’).

![]() For further information on ‘Drilling gas wells’ and ‘Types of gas wells and well pads’ download the GasFields Commission’s Gas Guide and Roadmap (see Chapter 7 – Construction Phase).

For further information on ‘Drilling gas wells’ and ‘Types of gas wells and well pads’ download the GasFields Commission’s Gas Guide and Roadmap (see Chapter 7 – Construction Phase).

Department of Resources ‘Directional Drilling’ fact sheet:

In 2020 a number of rural landholders raised concerns to the GasFields Commission and the State Government about the processes and potential impacts of directional drilling activities under landholders’ properties.

In response to these concerns and to clarify the existing regulatory framework the Department of Resources has released a ‘Directional Drilling’ fact sheet that sets out the regulatory requirements for resource authority holders to access private land to carry out directional drilling activities on adjacent land, and the landholder rights that would apply in that scenario.

![]() Download the Department of Resources’ ‘Directional Drilling’ fact sheet.

Download the Department of Resources’ ‘Directional Drilling’ fact sheet.

Importantly – the fact sheet outlines clear expectations of authority holders to engage early and openly with landholders around resource activities, whilst seeking to understand the impacts these directional drilling activities may have on landholders’ businesses.

As a landholder, you may be entitled to compensation as part of a Conduct and Compensation Agreement (CCA) to mitigate the impacts resulting from authorised petroleum and gas development activities on or under your property.

Queensland legislation provides the basis for determining any compensation entitlement and the amount is dependent on the impact the proposed resource company activities will have on your property and/or lifestyle.

Compensation is generally based on the following factors:

- The value of the land encumbered by the petroleum tenement;

- The intensity of the proposed works on the property;

- Loss in value due to construction and operation of the gas field on the property which is determined by market evidence;

- Proximity of the residence to gas field infrastructure; and

- Compensation entitlements vary depending on whether you are the owner or an occupier of the property.

Compensation can also include professional costs reasonably incurred by you in negotiating a CCA such as valuation, accounting, taxation, agronomist or legal fees. Resource companies each have individual approaches to determining compensation amounts. The term of activity on a property will affect the compensation amount payable.

The Commission’s flagship publication, the Gas Guide, catalogues pertinent information that landholders need to know about the various stages of petroleum and gas development in Queensland – including all the information landholders need to negotiate a fair and reasonable outcome should a resource company request to operate on your land.

![]() Download the Gas Guide for more information (see Chapter 5 – Land Access Agreements).

Download the Gas Guide for more information (see Chapter 5 – Land Access Agreements).

![]() For more information on ‘rights to compensation for a landholder if they have CSG activites on or under their land’,

For more information on ‘rights to compensation for a landholder if they have CSG activites on or under their land’,

visit the Commission’s Understanding compensation webpage.

![]() For more information on ‘Your entitlements to compensation’, visit the Business Queensland website: www.business.qld.gov.au.

For more information on ‘Your entitlements to compensation’, visit the Business Queensland website: www.business.qld.gov.au.

![]() For more information on compensation download the Department of Resources ‘A guide to landholder compensation for mining claims and mining leases’.

For more information on compensation download the Department of Resources ‘A guide to landholder compensation for mining claims and mining leases’.

![]() For more information on Conduct and Compensation Agreements download the Department of Resources ‘A guide to land access in Queensland’

For more information on Conduct and Compensation Agreements download the Department of Resources ‘A guide to land access in Queensland’

If a resource company wants to access private land, they will make contact with the landholder directly. Best practice by industry involves introductory discussions with a landholder to:

- Explain the planned project and what they want to do on the property – this could be petroleum and gas exploration, production, pipeline construction or installation of groundwater monitoring bores

- Understand the landholder’s biosecurity plan, property plan and long-term business plans

- Discuss the way the company intends to access the property and work through necessary constraints that the landholder may have

- Encourage landholder participation in any preliminary scouting activities.

![]() The introductory meeting should focus on learning about each other’s interests and potential logistical and ‘amenity’ challenges. Never lose sight of the fact that this could be the start of a long-term relationship – it helps to start with a positive attitude.

The introductory meeting should focus on learning about each other’s interests and potential logistical and ‘amenity’ challenges. Never lose sight of the fact that this could be the start of a long-term relationship – it helps to start with a positive attitude.

THE INTRODUCTORY MEETING IS AN OPPORTUNITY FOR LANDHOLDERS TO:

- Ask about the proposed infrastructure the resource company would like to construct on your land

- Discuss potential locations for infrastructure to assist the resource company in identifying possible locations for wells, gathering lines and other infrastructure

- Understand how the resource company will approach the construction and what they expect from you

- Discuss your property map and business plan (at least 5-10 year plan)

- Discuss your biosecurity management plan with the resource company, particularly to identify Appropriate points of entry and any other requirements for, or constraints to access (download the Commission’s Biosecurity Checklist)

- Discuss potential dates for the resource company to conduct preliminary activities to assist them in scheduling the work at an appropriate time.

The Gas Guide

The GasFields Commission’s Gas Guide brings together all the information landholders need to know about gas development into one concise, easy to read document – detailing everything from the awarding of exploration permits, Land Access and Make Good Agreements, right through to gas field rehabilitation.

The Gas Guide and Roadmap have been specifically collated to deliver landholders a clear and easy to understand guide of what to expect during each stage of engagement with petroleum and gas developments, on private land, in Queensland – including detailed information on what landholders can expect from both preliminary and advanced activities (see Chapter 4 – Engagement Phase). Download the Gas Guide and Roadmap for more information.

![]() To investigate current gas development activities, visit the GFCQ Interactive Gas Map which gives you access to view and download geospatial data/information relating to Queensland’s onshore gas industry activities in your local area.

To investigate current gas development activities, visit the GFCQ Interactive Gas Map which gives you access to view and download geospatial data/information relating to Queensland’s onshore gas industry activities in your local area.

Decommissioning, rehabilitation and surrender of resource authorities and infrastructure

At the end of the life of a resource authority, the holder must apply to surrender both the EA and the resource authority (other than an ATP which cannot be surrendered). The resource authority cannot be surrendered unless the relevant EA has been cancelled or surrendered. The extent to which the holder has complied with the conditions of the EA as well as the public interest must also be considered in the decision to approve any resource authority surrender.

Obligations prior to end of the resource authority or when an area ceases to be in the area of the authority

Before the end of the resource authority, obligations attach to the holder in relation to the infrastructure and improvements on the land in the area of the authority.

Decommissioning Wells

The holder of a resource authority has an obligation to decommission any petroleum well, water injection bore, water observation bore or water supply bore drilled by or for the holder before the tenure ends or the land on which they are located ceases to be in the area of the authority (i.e. in circumstances where the tenure is partially relinquished or cancelled).

A petroleum well is only decommissioned if it is done in the manner prescribed under a regulation. The well decommissioning standards are set out in the Code of Practice for the construction and abandonment of petroleum wells and associated bores in Queensland. Those standards are invoked by the Petroleum and Gas (Safety) Regulation 2018. The well abandonment objectives contained in the code are directed to:

- the isolation of aquifers from each other and from permeable hydrocarbon zones;

- the isolation of permeable hydrocarbon zones from each other unless commingling is permitted;

- seeing that permeable formations containing fluids at different pressure gradients and/or significantly different salinities are isolated from each other to prevent crossflow;

- seeing there is no pressure or flow of hydrocarbons or fluids at surface both internally in the well and externally behind all casing strings;

- recovery/removal of surface equipment so as to not adversely interfere with the normal activities of the owner of the land on which the well or bore is located; and

- the site being left safe and free from contaminants.

Despite being decommissioned, the holder has responsibility for any well or bore until such time when the petroleum tenure ends or the land ceases to be part of the authority. At this time, the State becomes responsible for the well or bore, unless the well or bore has been transferred to the landowner via an agreement.

Decommissioning Pipelines

The holder of a resource authority must decommission any pipeline within its area before the authority ends, or the land on which they are located ceases to be in the area of the authority.

A pipeline remains the holder’s personal property while the resource authority is in force. Section 540 of the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 provides that generally, it remains the personal property of the holder even if the authority ends, or the land on which it is located ceases to be part of the authority. Section 540 also provides that the holder, or former holder, may dispose of a pipeline that has been decommissioned under Section 559 to anyone else.

In the event that the holder no longer exists (i.e. there has been a disclaimer or it has been de-registered), the pipeline can be remediated under Chapter 10, Part 3 of the P&G Act – the abandoned operating plant framework.

Pipeline infrastructure remains the property of the previous authority holder despite the surrender of the authority. The Commission has identified that the provisions relating to the decommissioning of pipeline infrastructure described in section 540 is an anomaly when compared to the rest of the decommissioning provisions of the P&G Act. All other infrastructure is either removed from the land and/or the State assumes responsibility of it, pipelines remain the ownership of a third party.

The Commission recommends that the State amend the P&G Act so that section 540 and the decommissioning of pipelines is consistent with other decommissioning provisions in the P&G Act.

Equipment and Improvements

The resource authority holder also has an obligation to remove any equipment or improvements from the land before the day the authority ends or the day the land ceases to be in the area of the authority (whichever is earlier) unless the landholder otherwise agrees.

Equipment or improvements taken onto, constructed or placed on land in the area of a resource authority, for the purposes of the authority, remain the property of the holder while the authority remains in force.

However, if the holder of the resource authority fails to remove equipment or improvements, the State may authorise a person to enter land to remove it. At this point it becomes the property of the State.

State’s power to authorise entry to undertake activities after tenure has ended

The State also has a range of powers to authorise persons (including the former holder) to enter land under the P&G Act to remove equipment, decommission petroleum wells, remediate legacy boreholes, and comply with end of authority or area reduction obligations.

Standards for the rehabilitation of Coal Seam Gas (CSG) infrastructure

Specific obligations and conditions in relation to the construction, operation and decommissioning of petroleum and CSG infrastructure are imposed on authority holders through an EA granted under the EP Act.

The EA includes rehabilitation requirements that must be achieved before the EA can be approved for surrender and the relevant petroleum and gas authority can be returned to the State. These requirements will vary depending on the condition of the land and its use prior to the commencement of the authorised activities.

Generally, rehabilitation requirements require any disturbance caused by the authorised activity to be rehabilitated, leaving a site that will not cause environmental harm and that is suitable for a future use.

The surrender process includes an assessment of compliance with the EA conditions in relation to rehabilitation. For this reason, the conditions of the EA are critical in determining the final rehabilitation outcome including which ‘site features’ may remain when an EA is surrendered.

The surrender of an EA may be approved where site features remain on the site. The site features include both legacy infrastructure (e.g. pipelines and wells) as well as infrastructure that the landholder has agreed to use and take responsibility for (e.g. water bores and dams).

The residual risks associated with any legacy infrastructure transferred to the landholder by agreement are not considered as part of the surrender process. To clarify, if the landholder has agreed to take responsibility for any legacy infrastructure, that infrastructure is not considered in the evaluation of residual risk calculations.

Once all required rehabilitation work under the EA is completed and the remaining residual risks are calculated and paid, an EA can be surrendered, and the associated tenure surrendered. However, before the tenure can be surrendered, the tenure holder must fulfil all of the conditions of the resource authority as well as the rehabilitation conditions of the EA.

Once the tenure and the EA are surrendered, all obligations of the resource authority holder cease.

What protection does a landholder have for any future potential impacts?

Responsibility for legacy infrastructure

In the event of the failure of legacy infrastructure causing environmental damage, the responsibility generally rests with the State to undertake the relevant remediation activities to repair, manage and/or prevent any further environmental damage. Exceptions to this position may include:

- where the State has lawfully transferred ownership of a decommissioned gas well or bore to the owner of the land on which the well or bore is located or the holder of a geothermal tenure or mining tenement the area of which includes that land;

- where ownership in a decommissioned pipeline is retained by the relevant tenure holder; or

- where the relevant tenure holder has disposed of a decommissioned pipeline to another person.

Depending on the circumstances, the residual risk fund may be applied.

Relevantly, the State has the necessary powers to authorise and/or undertake remediation activities required in relation to legacy infrastructure. This includes broad powers under the abandoned operating plant framework in Chapter 10, Part 3 of the P&G Act. It also includes the power in section 294B to authorise a person to remediate certain bores or wells and to rehabilitate the surrounding area in compliance with requirements prescribed by regulation.

The issue of liability for personal injury, property damage or other loss caused by legacy infrastructure will ultimately depend on all the relevant facts and circumstances. These situations need to be dealt with on a case by case basis. If harm is caused to a third party as a result of a failure of legacy infrastructure, the individual circumstances that led to the harm being caused will determine where legal responsibility lies.

However, in most circumstances landholders will generally not be liable for harm caused by or arising from the failure of any legacy infrastructure on their properties, provided the landholder’s actions did not cause or contribute to the failure or the resulting harm. In most circumstances the regulatory framework is designed so that the State takes responsibility for dealing with issues arising from legacy infrastructure.

The Queensland Government Insurance Fund

The Commission has undertaken discussions with the Queensland Government Insurance Fund (QGIF) in relation to the States responsibility to pay compensation to third parties for personal injury, financial loss or property damage as a result of a failure of legacy infrastructure.

The Commission understands that if injury, loss or damage occurred to a third party as a result of the failure of legacy infrastructure and it was found the failure was the direct fault of the State, then the State would be liable to pay compensation. The Commission acknowledges that each claim against the State would need to be considered and investigated on a case by case basis to determine the contributing factors including:

- the nature of the failure;

- the cause of the failure;

- the actions that the State did or did not take that caused fault; and

- the actions that the third party did or did not take that contributed to the injury, loss and or damage.

![]() For more detail around regulatory protections afforded to landholders who host onshore gas activities (including legacy CSG infrastructure) view the Queensland Government’s ‘Public liability for petroleum, gas and CSG infrastructure’ webpage.

For more detail around regulatory protections afforded to landholders who host onshore gas activities (including legacy CSG infrastructure) view the Queensland Government’s ‘Public liability for petroleum, gas and CSG infrastructure’ webpage.

![]() Download the GasFields Commission’s ‘Long-term public liability for remediated coal seam gas infrastructure on private property’ Issues Paper.

Download the GasFields Commission’s ‘Long-term public liability for remediated coal seam gas infrastructure on private property’ Issues Paper.

Who is the Land Access Ombudsman?

The Land Access Ombudsman (LAO) provides a free, fair and independent service to investigate and resolve land access disputes in Queensland. If you have an existing Conduct and Compensation Agreement (CCA) or Make Good Agreement (MGA) and believe the other party has breached the conditions, the LAO can help resolve your dispute by:

- offering an opinion on the merits of each party’s position;

- advising on a way forward; and

- making practical recommendations based on the specific facts and circumstances of each dispute.

To do this, the LAO gives both parties the opportunity to discuss their concerns and take the time to understand all aspects of the issue without taking sides. The LAO aims to resolve disputes quickly and efficiently, with as little formality and technicality as possible.

LAO’s services are free to all parties, don’t require you to have legal representation and can help you avoid the stress and cost of litigation. LAO can also travel to you if needed. Both landholders and resource companies can refer disputes to the LAO.

![]() Download the Land Access Ombudsman’s ‘About Us’ Fact Sheet for more information.

Download the Land Access Ombudsman’s ‘About Us’ Fact Sheet for more information.

How does the Land Access Ombudsman differ from the GasFields Commission?

Established as an independent statutory body in 2013, the Commission’s purpose is to manage and improve the sustainable coexistence of landholders, regional communities and the onshore gas industry in Queensland. The Commission manages sustainable coexistence in petroleum and gas producing regions of Queensland, and will continue to do so as the industry expands into new and emerging basins.

The Commission’s 14 functions are set out in the Gasfields Commission Act 2013. These 14 legislated functions (see About Us) can be summarised into three ‘core objectives‘:

- FACILITATE effective stakeholder relationships, collaborations and partnerships to support education and information sharing related to Queensland’s onshore gas industry.

- REVIEW effectiveness of the implementation of regulatory frameworks related to Queensland’s onshore gas industry.

- ADVISE agriculture and gas industry peak bodies, government ministers and regulators, landholders and community groups on matters relating to sustainable coexistence, leading practice and management of Queensland’s onshore gas industry.

Drawing on its wealth of experience in the development of the gas industry and by collaborating with other relevant entities, the Commission provides a range of support to communities and landholders, primarily through education and engagement. This education and engagement occurs through direct contact with individual landholders and via Commission facilitated webinars, information sessions, publications (The Gas Guide, Shared Landscape Report, On New Ground), pop-up shops, meetings and workshops. It should be noted that the Commission does not engage in individual negotiations between landholders and gas companies, but rather provides communities and landholders with the information and support they need to make informed decisions and achieve good outcomes.

![]() Download the GasFields Commission / Land Access Ombudsman ‘What We Do’ Fact Sheet for more information.

Download the GasFields Commission / Land Access Ombudsman ‘What We Do’ Fact Sheet for more information.

As of 30 June 2020, a total of 15,890 coal seam gas (CSG) and petroleum wells had been drilled in Queensland (across all tenure types) since records began in the 1960s.

Of these 12,356 target CSG with 96% of these located within the Bowen and Surat basins, with the remainder (514 wells) found in other basins. In FY20 alone, there were 975 petroleum and CSG wells drilled in Queensland.

![]() For further information on ‘CSG wells’ download the GasFields Commission’s ‘Shared Landscapes – Industry Snapshot’ Report (see Chapter 2 – CSG & PETROLEUM WELLS).

For further information on ‘CSG wells’ download the GasFields Commission’s ‘Shared Landscapes – Industry Snapshot’ Report (see Chapter 2 – CSG & PETROLEUM WELLS).

![]() To investigate current gas development activities, visit the GFCQ Interactive Gas Map which gives you access to view and download geospatial data/information relating to Queensland’s onshore gas industry activities in your local area.

To investigate current gas development activities, visit the GFCQ Interactive Gas Map which gives you access to view and download geospatial data/information relating to Queensland’s onshore gas industry activities in your local area.

As at the end of 2020, there were approximately 8,600 coal seam gas (CSG) wells in the Surat Cumulative Management Area (Surat CMA) that are either currently producing gas or have been completed as production wells and are yet to be brought into production.

Of these, 84% are in the Surat Basin and the rest are in the southern Bowen Basin. There are also an additional 500 wells outside CSG production areas constructed for exploration or testing purposes.